Keep exploring here

Michel Durand Nolett

Michel is deeply engaged in knowledge transfer and dissemination. He shares his time working for the Wabanaki communities of Odanak and Wôlinak, and being invited to conferences and workshops across Quebec and Canada. The knowledge and stories he shared were so diverse, that they are featured at various places on Circle of Voices: here he talks about his practice with the healing drum, and here about the traditional Abenaki practice of ash pounding. His spiritual practice is deeply connected with the land, as ancestral Indigenous practices usually are. I also interviewed him here, because he works as land manager in Odanak, and founded the Environmental Office with Luc.

How and where did you grow up?

«I was born here, in Odanak, and my father worked outside, he was a cook on oil tankers. When I was born, there was my mother, my grandmother and my great grandmother. We all stayed in the same house. I was very lucky to have a grandmother and a great grandmother who taught me a lot.»

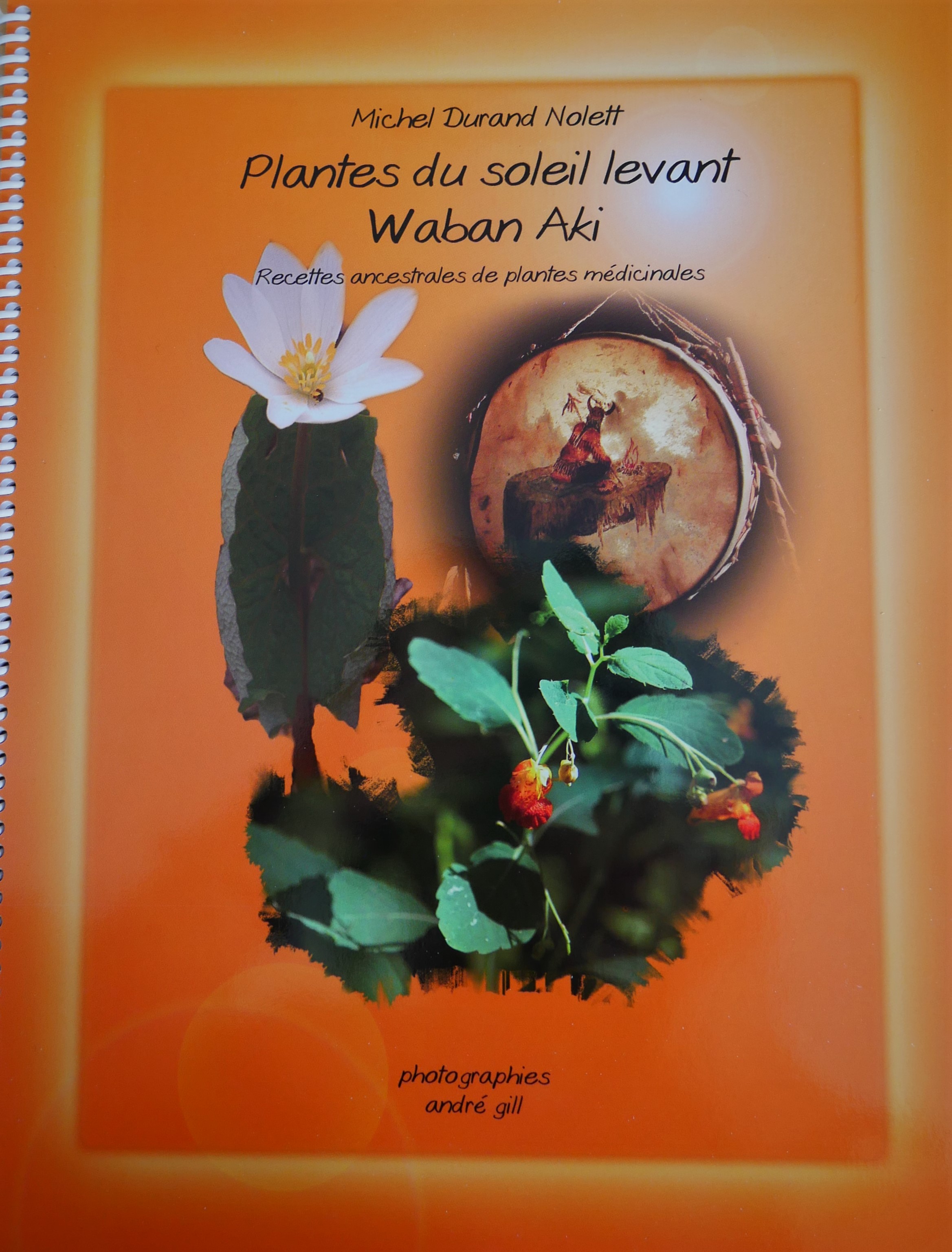

«My grandmother taught me a lot about herbal medicine. I was going to find some medicinal plants for her, she would tell me "I need such a plant", she would show it to me. My playground was the surrounding forest. I used to go outside, and at one point I would remember that I had put the plant in my pockets, so I would take it out. (...) Then I knew where to find some, so I could bring plants back for her. Finding medicinal plants was like a game. Why? I didn't know what it was for until the day I tasted her medicine... Then I knew what were the plants used for that I was foraging, it was a taste to be discovered!»

What is your place in the community in terms of traditional knowledge?

«On the plant side, I'm unfortunately one of the only ones... There aren't many, maybe one or two other people who use plants sometimes. But to disseminate information and disseminate traditional knowledge about plants, I am the only one. When there is a workshop on medicinal plants, when there is a conference on medicinal plants, I’m going to be there. The other people even if you ask them, they will say, "No this is for the rest of us, our little family, it ends there." I had a request at one point from the health center, the Odanak Band Council to write down my traditional knowledge, and what I gathered from the other elders who still remained in the community, who could still do it. I accepted. It was easy for me, all the seniors, I knew them all.»

«I came to do research on traditional wabanakiak medicine. How the Wabanakiak lived back then, on the territory, how did they heal themselves, what plants they took. I went further, even on the spiritual side of things. I pushed more on that side. And what helped me a lot? It took less time in my research because I had my great-grandmother, who she was born in 1873. She died, she was 100 years old. And my pleasure was to talk to my great grandmother and to ask her: "when you were young, how was it?". Make her tell her story when she was a little girl and she was in the forest with her parents. There she told me stories, and she told me about plants too.»

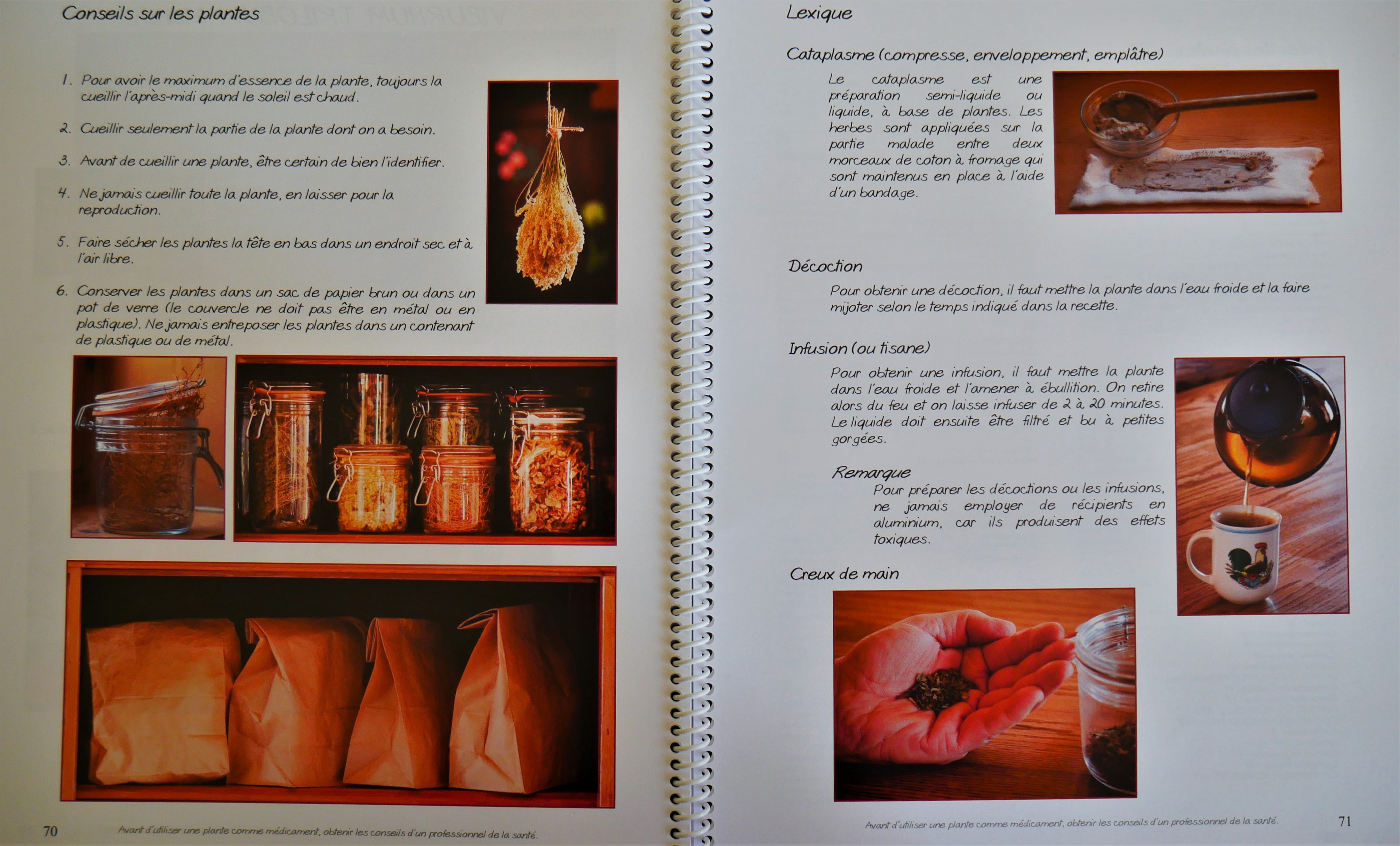

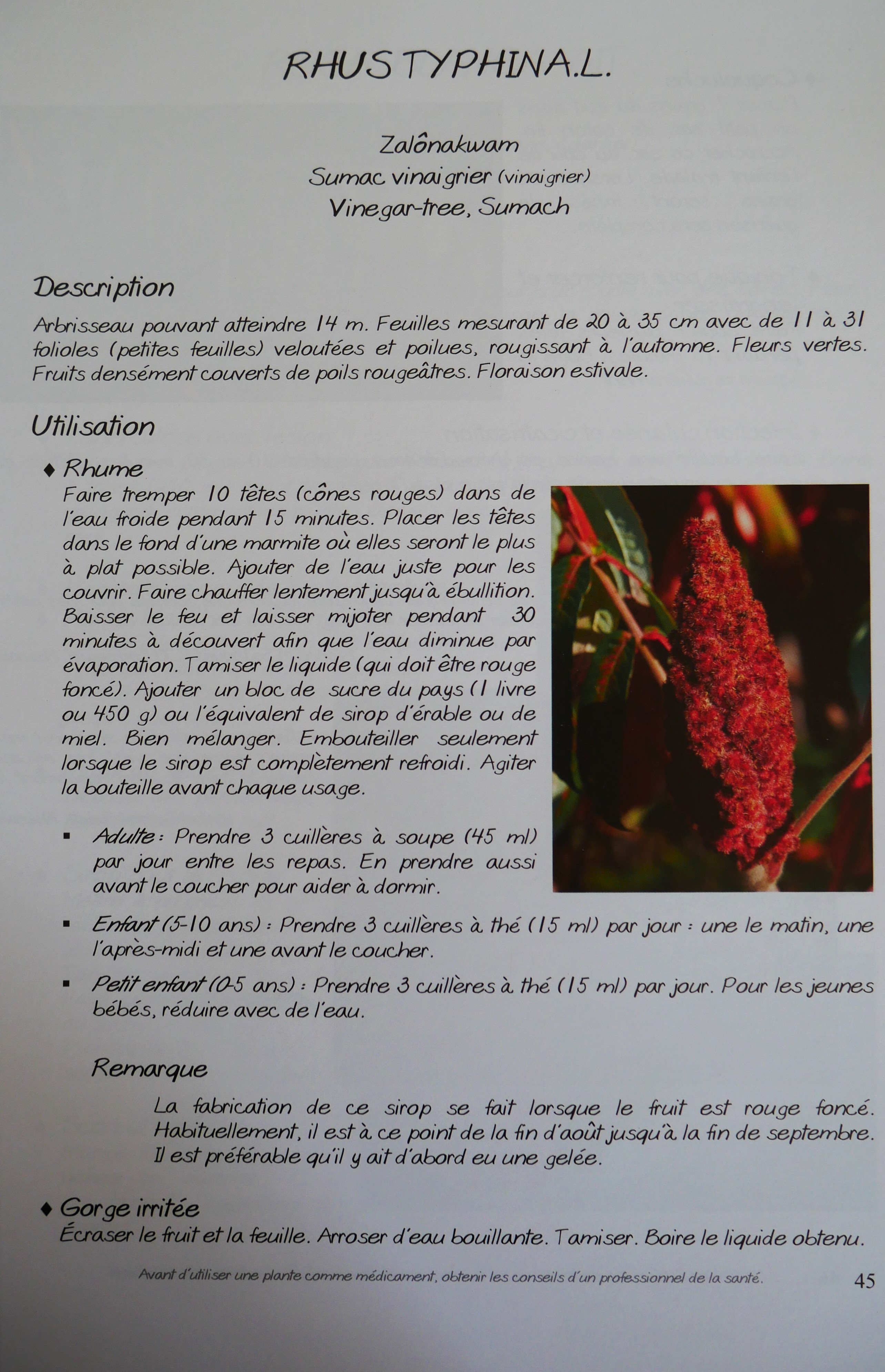

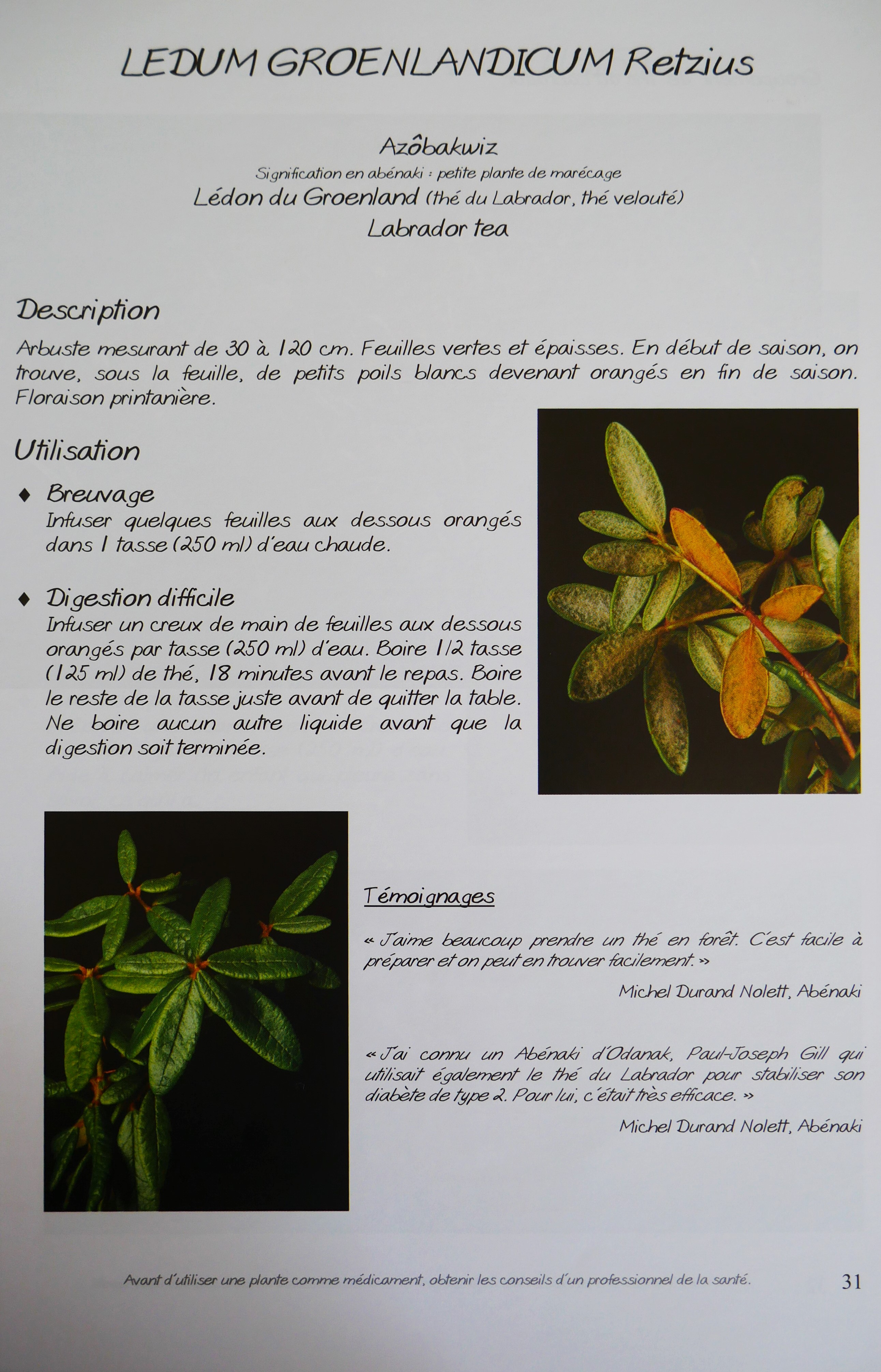

Pages from the book curated by Michel

Could you tell me more about the Medicine Wheel and its pratical application?

«Everyone can have their interpretation of the medicine wheel. The base is there for everyone: you steer your medicine wheel in all four directions, north, south, east, west. Like the healing drum: when you build it, you lay it flat, upside down, and it's a portable medicine wheel. Everyone is going to design their medicine wheel. I am not a uniformist, go ahead with your heart, your mind, do things and it will be okay. It's like a pie plate. You got your plate, and you got your crust, after that it's up to you what to put on it. If you put strawberries and raspberries, instead of apples... You're still going to have a pie, but that will depend on what you want to have as a pie.»

What is spirituality for you, how do you live it?

«I have been serving mass for years. I think I must have been 5, 6 years old when I started, I was a very little guy. During the week, early in the morning, you had to go to church, there were masses every day at that time. I have always respected my grandmother in these beliefs. I followed him a lot at one point. Then I let go. I am a believer, but not by the definition of the Catholic Church. I believe in a superior being who is a being of light or a being of... call it whatever you want. Indigenous peoples at the time, they believed in a superior being, they said the Creator. They didn't say God or Jesus, they didn't know, they didn't yet have that notion. There was a Creator, something that created what you have here. And they thanked. some people said it was the sun that did that. They were not wrong, without sunlight plants cannot grow. They thanked the sun for giving food, the plants that were there: it was the creative sun. But when you look at that, at the end of the day, we're all creators. It's up to you to create, to create things, to create the wellbeing in you.»

How do you envision the future of young First Nations in Quebec and Canada?

«I think there are a lot of young people making their mark today. Thanks to parents who have gone further than they have been. In the sense that, young people today have a much easier time going to schools, colleges, and universities. In the community here, it’s special, Odanak is the most educated community across the province of Quebec. Before, Indigenous peoples, they shouldn't be educated too much, they had to stay there, in the background. Anyway, they made reservations about that, we were put on reservations. The reserve is a prison. Besides, that's why, you've noticed from the start, I'm not talking about reservations, I'm talking about communities. Young people are very involved in culture. You noticed here in Odanak, you met some young people who are involved. Like Luc with the black ash, the smoked sturgeon he does. This is culture. I'm proud to see that, that young people get involved in culture. Keep it alive. We are here, we were there, we will still be here tomorrow.»

What are the stereotypes and prejudices which you can't stand anymore and would like to fight against?

«A lot of people still categorize Indigenous peoples. One example, they see a drunk native: "they're all alcoholics!" No. It is still present in many mindsets, to generalize for whole Nations in relation to one or two individuals. Just because you're aboriginal and drunk doesn't mean that all aboriginals in the province of Quebec are drunk. This has nothing to do with it. When people don't know something, laugh at it or ridicule it.»